While the treatment of every disease, illness or health problem is unique, this article hopes to convey my ideas on the basic framework on which they are based. This article is in the process of being written.

Introduction

To both patients and care providers, treatment is the most important aspect of the care of a patient. Even so, the treatment procedure itself and its desired outcome is dependent on the proper conduct of other parts of the the clinical care process. Patients are often surprised that many procedures must be done before treatment is given and more again afterwards. Care providers often want to get on with treatment without giving due attention to the other necessary clinical care processes that comes with it. It must be stressed that although treatment is the main task, it’s success is dependent on proper execution of the other clinical care processes.

Place of Treatment in the Clinical Care Process

The type of treatment given depends on the diagnosis. The basic framework of treatment is:

Diagnose>Treat>Review

The diagnosis has variable degrees of certainty and accuracy. As such, at the earlier phases of care the treatment will consist of general measures. Specific treatment is offered only when a specific diagnosis is obtained. The effects of the treatment on the progress of the disease are reviewed and changes are made accordingly.

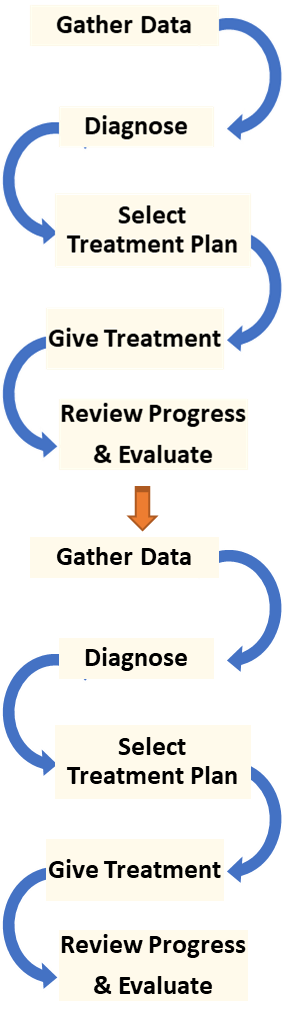

Iterative Nature of the Treatment Procedure

The achievement of overall objectives of treatment depends on how well other procedures in the care cycle are performed. In most cases, the final objective can be met only through a series of purposeful repetitions or iterations of various procedures. It is therefore necessary that during the entire episode of the care of a patient, the procedures of interview, examination, tests, diagnosis, plan, treatment and evaluation are carried out as repeating cycles. The iteration of clinical data gathering and investigations result in the acquisition of more comprehensive and accurate information, leading to a clearer diagnosis. The diagnosis is the key to the selection of the correct treatment plan. Variations in the treatment regimen are made based on the results shown by the information gathered from the processes of monitoring and progress review. This iteration (fine-tuning) of the treatment enables a more appropriate, effective and safe outcome.

Treatment Plans

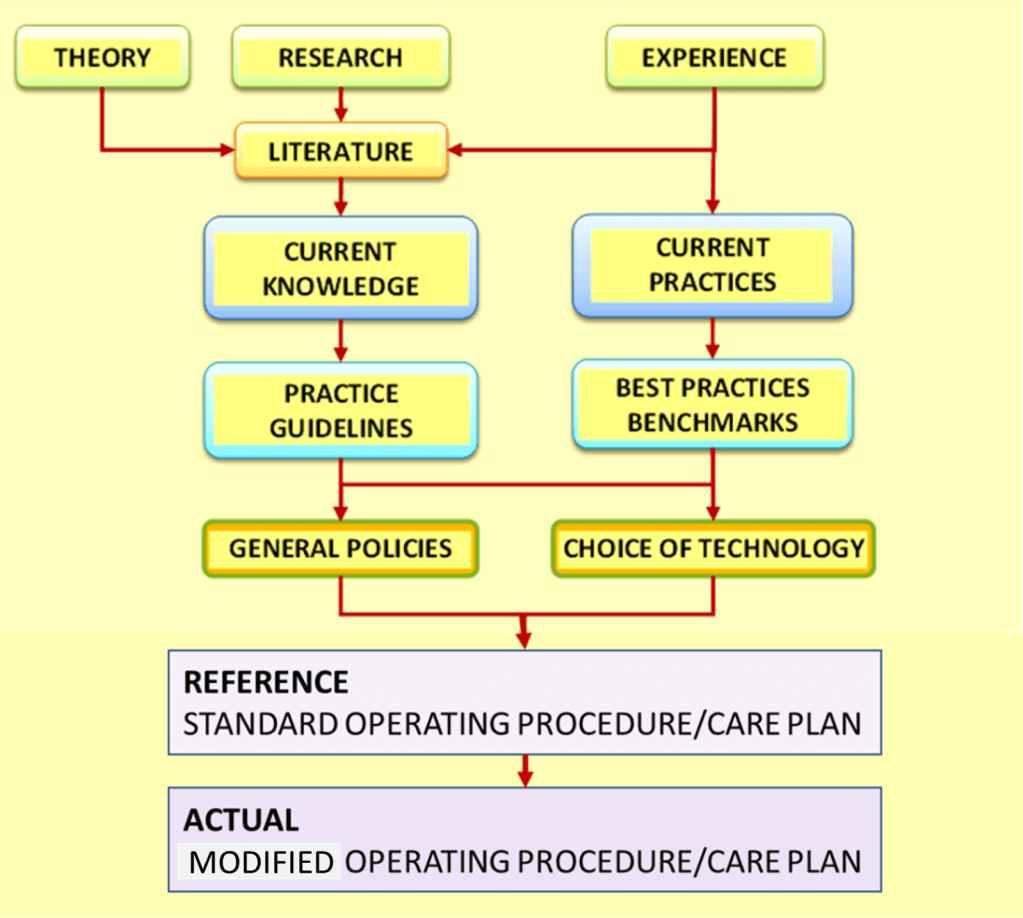

Because of their training, healthcare professionals are capable of planning the care of a patient spontaneously on their own. Yet, it is much better if the treatment follows a carefully designed standardized plans termed as SOP/Care Plans.

The reference SOP/Care Plan is a guide for the care of various diseases, syndromes or symptom complexes. Standardization promotes conformity to the fundamental content and methods of the care of patients among all care providers. As part of the plan, the roles of care providers within the team are are assigned, thus promoting cohesion. In clinical patient care, extreme rigidity is avoided by introducing variations into the plans when they are first written. Furthermore, care providers have the freedom to alter practices in response to peculiar situations and requirements.

Philosophy, Approach and Strategy of Treatment

When treatment is given, it should be with the intention of imparting benefit to the patient. It should not be given just for sake of doing something. The care provider must have confidence that the treatment regimen chosen is appropriate i.e. has the potential of providing a safe and effective outcome. But then for each method of treatment, he/she can only make an assumption that a beneficial result can be obtained. This is because the outcome depends on a multitude of factors. Hence, the clinician must have clear knowledge regarding the methods, regimens or protocols and their limitations. He/she must be aware of scientific basis for their acceptance. This approach is said to be the practice of evidence based medicine.

In making decisions about the care of individual patients, he/she integrates what is known through available evidence with his/her own clinical experience and fashion the treatment plan accordingly. The use of standardized care plans/standard operating procedures, would be of great help in this regard.

Objectives of Treatment

Clinical Objectives

Before treatment is initiated, the objectives i.e. the desired outcome must be determined. The choice of the appropriate treatment plan, is made based on the type or nature of the disease, illness or health problem plus its :

- severity

- grading

- stage

- effect on the patient

- availability of treatment options

Treatment objectives vary according to the disease characteristics mentioned above. These objectives are summarized by the dictum “to cure sometimes, to relieve often, to comfort always”. Depending on the nature of the disease and the objectives, the treatment strategy can be one of three categories:

- Cure

- Restriction of effects and prevention of deterioration

- Palliation

When there is potential for cure or cessation of the disease processes, a concerted attempt is made to achieve it. However, this potential is constrained by the level of severity at the point of presentation. Virulent disease may be cured if the patient comes early for treatment. Complete resolution of potentially curable disease may not be achieved if the disease too far advanced. However, cure is not the only objective of treatment. Even when elimination or cessation of the disease is not possible, many other beneficial therapeutic interventions that provide relief or comfort can and must be offered.

Care providers are concerned about the quality of care given to patients in terms of :

- Effectiveness,

- Appropriateness,

- Safety,

- Timeliness and,

- Acceptability.

Treatment is effective if the right plan is chosen and then properly executed. Effectiveness is relative to the severity of the disease. The desirable outcome may take a greater effort and longer time to achieve. Failure to gain intended results may be caused by the mismatch between treatment regimen with the disease type. Also, it must be fitting with the patient’s general condition. Depending on situations, a care provider may not be able to choose the right option because he/she is unable to carry it out or the requisites are unavailable at his/her facility. They must then act as the advocate for the patient by consulting other caregivers and when necessary referring the case to another care provider or healthcare facility.

Service Delivery Objectives

From a service delivery perspective, both the care providers and the managers of the patient care facilities need to treat the patient as a customer. While the aspects they focus on and the approach may be different, the service given must serve the needs of the patient.

Managers must consider the following aspects of the quality of the service given:

- productivity,

- efficiency,

- responsiveness,

- availability,

- convenience and

- cost-effectiveness (viability).

Many of these factors are interdependent. Patients tend to seek treatment early if the location is accessible and cost of the treatment is affordable. Even so, the patient will comply with the treatment only if it is culturally acceptable. Efficient systems and processes can make services convenient, less costly and therefore more affordable. Efficiency on the part of service providers enable care to be given within the stipulated time, thus minimize delays and promote timeliness. Patients are also appreciative when service staff are attentive, considerate and give appropriate response to their needs

Safety and Risks

Safety overrides all other considerations as advocated by the dictum “First do no harm“. The care provider when faced with a health problem in a patient, may decide not to do something, or even to do nothing, than to risk causing more harm than good. The healthcare provider must consider the obvious harm that any intervention might pose as opposed to an uncertain beneficial effect.

All treatments have variable degrees of risks. Some detrimental effects are unavoidable while others occur uncommonly. The propensity of their occurrence are also dependent on the type of patient. Despite this rather than avoiding treatment altogether, the care provider has to weigh the benefits against the risks. It is essential that the care provider is familiar with the harmful effects of the treatment modality he/ she intends to use. Above that, he/she must be aware of the situations when they would likely occur (the risk), the measures to take to prevent or minimize them and be ready to intervene when they happen. The care provider must inform patients regarding the possibility of unwanted and unexpected effects. Therefore, in most instances care processes must be performed only with the informed consent of the patient.

Occurrence of detrimental effects depends on the treatment processes as well as the system in which care is given. Anticipating side-effects and complications of treatment plus their prevention is part and parcel of the due diligence expected of care providers and the facility that they work in. Omitting them may be considered as professional negligence thus increasing the likelihood of litigation. However, the threat of facing litigation should not deter care providers from offering treatment that has the potential for providing benefit to the patient. The medico-legal aspect of managing the possibility of harm to patients is called “Risk Management“.

Strategies, Methods and Modalities of Treatment

A wide variety of strategies, methods and modalities are available to the care provider. Their selection depends on the type of disease and the condition of the patient which in turn determines the outcome that can be hoped for. The possible strategies include:

- Remove or minimize (mitigate) effects of illness

- Prevent deterioration or recurrence (secondary prevention)

- Restore or improve the functions or physical appearance that has been impaired due to the illness (tertiary prevention)

- Avoid or minimize complications of treatment

- Promote the improvement or maintenance of good health status

The content of the treatment in each of the above strategies may be a mix of the following options:

- Symptomatic therapy

- Supportive therapy

- Preventive therapy

- Rehabilitative therapy

- Health Promotion

The selection of above the options, their sequence and priority will depend very much on the type, severity and effects of the illness.

Choice, Indications and Contraindications

When the use of certain modalities or regimens have equal potential of being effective then the care provider may choose one that is more convenient, less costly, more easily available or more acceptable to the patient. Above all, safety should never be compromised.

There must be a valid indication (i.e. reason) to use a certain treatment plan, regiment or modality. As a rule, the treatment must match the diagnosis. At he same time, its effectiveness and safety is also dependent on the condition of the patient.

Even if a procedure or medication is known to be effective based on the diagnosis, it may be contraindicated when certain situations or circumstances are present. Contraindications can be relative or absolute. The consideration is whether the risks of treatment clearly outweigh the benefits. When a safer alternative is available it should be chosen. If there is no other alternative, the care provider may initiate the treatment regimen with utmost caution and be ready to abandon it when there is evidence of harmful effects.

Risks can be contributed by innate characteristics like age, sex, known allergy or genetic conditions. A drug may be detrimental on growth, immature system cannot cope with it. A drug may be contraindicated in pregnancy due to the risk of birth defects. Therefore care must be made when giving drugs to fertile women. Risks can arise because of the patients general health, presence of pre-existing illnesses or being on a medication.

Certain risks can be modulated through prophylaxis (e.g. antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent endocarditis, prior steroid therapy in anticipation of an allergic reaction). If the danger is posed by impaired health status arising from pre-existing illnesses (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, bronchial asthma etc.) attempts should be made to improve the condition of the patient by optimizing the treatment for them. When there is possibility of a medication being introduced interacting with a drug that the patient is already taking, care is made through omitting of the drug or reducing the dose.

Efficacy vs Effectiveness

The evidence in evidence-based medicine is based largely on trials. An intervention is said to be efficacious if it is able to produce the expected result under ideal circumstances usually found in trials. Efficacy is not an adequate basis for adoption in practice. The intervention must be proven to be effective i.e. have beneficial effect under “real world” clinical settings as shown by clinical trials or experience when used on a considerable number of patients and over an adequate period. Clinicians must exercise care when deciding to adopt new findings or ideas being introduced.

Place of Treatment in the Phases of Care

The processes in the care of the patient are grouped and sequenced into phases. Treatment is a part of every phase but the purpose may be different. As care progresses through the phases, the care provider need to make changes to the objective, choice of modality and the methods used.

At the earliest phase, the purpose of treatment is mainly providing support and relief of symptoms. When a definitive diagnosis is arrived at, the appropriate treatment is initiated. Initially, the treatment is said to be expectant. The care provider anticipates certain benefits and possible detrimental effects that he/she must look out for through observation or monitoring of various parameters. Then, depending on whether the results are encouraging or otherwise, the treatment regimen is continued, modified or terminated and replaced. These actions are repeated (iterated) until an optimal result is obtained.

The duration of treatment depends on the nature of the disease. If there is a possibility of cure the treatment is continued (iterated) until the evidence of cure is clear. If the aim of treatment is to halt disease advancement, recover functions, prevent deterioration and minimize symptoms, then the treatment is maintained when the optimal effect of the modality (dosage, frequency, duration) is obtained.

The treatment is stopped if cure is achieved or if no further benefit can be hoped from it. For most chronic diseases, care continues with iterations of treatment and monitoring. Even, so reviews should be made at suitable intervals.

Change of Treatment with Change in Diagnosis

Treatment is dependent on diagnosis. Because the level of accuracy of the diagnosis becomes increasingly certain with more information gathered, the treatment package varies according to the current working diagnosis.

| Working Diagnosis | Objectives | Care Plan |

|---|---|---|

| LOW SPECIFICITY A. Symptom complex B. Clinical Syndrome C. Diagnostic Related Group D. Clinical Syndrome | a. Symptom relief b. Resuscitation c. Stabilization d. Obtain sufficient data to arrive at diagnosis | Care plan for Phase of Determination of Diagnosis and Early treatment a. Data gathering to obtain diagnosis — Clinical data gathering — Investigations b. Early Treatment |

| HIGH SPECIFICITY a. Specific Disease /Illness/Health Problem b. Variant of Illness | Cure or Containment or Palliation | Specific Care Plan – Confirmation of diagnosis – Initiation of Care Plan – Optimization – Maintenance |

Care plans with different objectives and content need to be designed for different levels of accuracy of diagnosis. When the level of accuracy is low the aim is to provide symptom relief, resuscitation, and stabilization. When the diagnosis can be ascribed to a specific disease then a specific plan or regimen for it can be initiated, If information obtained points to specific variant of the disease, then the treatment must be modified accordingly.

Modalities of Treatment

Modalities are the different therapeutic techniques, approaches, or processes used to treat diseases, illnesses or heath problems. The type of modalities includes:

- Medication therapy

- Surgical therapy

- Physical therapy

- Psychotherapy

- Nursing

While all these techniques are used to some extent by most healthcare professionals, some are used a lot more by certain categories. Almost all clinicians use medication as part of therapy. The surgical modality is not used just by surgeons. Cardiologists, interventional radiologists and endoscopists use variations of the surgical technique. Psycho-social aid is beneficial when added to the care of all types of patients.

The safe and effective use of each of the above modalities is dependent on the fulfillment of certain requisites. Therefore, every healthcare professional need to be familiar with them.

Plans, Regimens and Protocols.

Plans describe the general approach to treatment. It prescribes the mix of modalities that has been proven effective in achieving optimal results. It includes indications and contraindications, requisites, sequence and layout of the procedures involved. Regimens usually delineate the actions taken for a particular modality (medication, surgery, therapy etc.). Protocols are specific instructions on how to carryout a certain procedure or action.

Medication Therapy

Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field. It relies on the science of pharmacy and pharmacology for continual advancement. The healthcare professional with detailed detailed knowledge about drugs is the pharmacist. However the safe and effective use of drugs is the responsibility of the pharmacist alone.

Safety and Effectiveness of Medication

Clinicians use drugs that have been proven to be safe and effective. New drugs undergo trials under very controlled conditions to a limited number of persons. When they show beneficial effects under these circumstances they are said to be efficacious. Further trials are then made to show that the benefit and safety can be achieved on a larger population of patients under ordinary clinical settings. The drug can then be said to be effective.

Clinicians must follow strict procedures when using drugs.

The Medication Procedure

The procedure of using drugs for treatment consists of a sequence of steps performed by different care providers. The three major steps are:

- Prescribing

- Dispensing

- Administration

These procedures are devised based on an understanding of the behavior of drugs plus the responses of the human body and the disease process to them.

Pharmacodynamics

The biochemical, physiologic, and molecular effects of drugs on the body is termed as the pharmacodynamics of the drug. Drugs usually work by binding to the receptors of cells of organs of the body causing stimulation or antagonizing of the physiological effects. or receptors invading organisms. It can also work by interacting harmful chemicals that accumulate in the body from internal or external sources. The concentration of the drug at the receptor site influences the drug’s effect.

Pharmacokinetics

The way a drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolised, and excreted is termed as pharmacokinetics. These properties studied and determined in trials are applied in clinical practice to achieve the optimum level of the drug that is both effective and safe. This level is dependent on the dose given, the route of administration, how the body interacts with the drug and how the drug is removed from the body.

It is usually not possible to measure drug concentrations at their receptor sites. However because there is a strong correlation between drug concentrations in the blood and their pharmacologic responses at the site of action, it is useful to monitor the blood level of the drug.

Prescribing

Clinicians should order drugs either by their generic (chemical names) or the proprietary names. They need to define the route of administration, formulation, and dose.

Prescribing Medication

- Route

- Name of drug

- Dose

- Route of administration

- Urgency,

- Frequency

- Duration

- Other comments

Dosing: Therapeutic index / window

The therapeutic index (TI; also referred to as therapeutic ratio) is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug. It is a comparison of the amount of a therapeutic agent that causes the therapeutic effect to the amount that causes toxicity.[1] The related terms therapeutic window or safety window refer to a range of doses optimized between efficacy and toxicity, achieving the greatest therapeutic benefit without resulting in unacceptable side-effects or toxicity.

Dispensing of Medication

Administration of Medication

Administration by Doctors

Administration by Nurses

Medication in Psychiatric Disorders

- treat different types of mental health problem

- reduce the symptoms of mental health problems

- prevent the return of mental health problems and their symptoms (also known as relapse).

The main types of psychiatric medication are:

- antidepressants

- antipsychotics

- sleeping pills and minor tranquillizers

- lithium and other mood stabilizers.

Execution of plans

Response to unforeseen or unplanned events

Medical/drug therapy. Use of antibiotics

Administration of Medication

The Surgical Modality

Surgical service and the surgical method

The Aim of Surgery

Work to correct the problem in body then proceeds. This work may involve:

- excision – cutting out an organ, tumor,[14] or other tissue.

- resection – partial removal of an organ or other bodily structure.[15]

- reconnection of organs, tissues, etc., particularly if severed. Resection of organs such as intestines involves reconnection. Internal suturing or stapling may be used. Surgical connection between blood vessels or other tubular or hollow structures such as loops of intestine is called anastomosis.[16]

- reduction – the movement or realignment of a body part to its normal position. e.g. Reduction of a broken nose involves the physical manipulation of the bone or cartilage from their displaced state back to their original position to restore normal airflow and aesthetics.[17]

- ligation – tying off blood vessels, ducts, or “tubes”.[18]

- grafts – may be severed pieces of tissue cut from the same (or different) body or flaps of tissue still partly connected to the body but resewn for rearranging or restructuring of the area of the body in question. Although grafting is often used in cosmetic surgery, it is also used in other surgery. Grafts may be taken from one area of the person’s body and inserted to another area of the body. An example is bypass surgery, where clogged blood vessels are bypassed with a graft from another part of the body. Alternatively, grafts may be from other persons, cadavers, or animals.[19]

- insertion of prosthetic parts when needed. Pins or screws to set and hold bones may be used. Sections of bone may be replaced with prosthetic rods or other parts. Sometimes a plate is inserted to replace a damaged area of skull. Artificial hip replacement has become more common.[20] Heart pacemakers or valves may be inserted. Many other types of prostheses are used.

- creation of a stoma, a permanent or semi-permanent opening in the body[21]

- in transplant surgery, the donor organ (taken out of the donor’s body) is inserted into the recipient’s body and reconnected to the recipient in all necessary ways (blood vessels, ducts, etc.).[22]

- arthrodesis – surgical connection of adjacent bones so the bones can grow together into one. Spinal fusion is an example of adjacent vertebrae connected allowing them to grow together into one piece.[23]

- modifying the digestive tract in bariatric surgery for weight loss.

- repair of a fistula, hernia, or prolapse.

- repair according to the ICD-10-PCS, in the Medical and Surgical Section 0, root operation Q, means restoring, to the extent possible, a body part to its normal anatomic structure and function. This definition, repair, is used only when the method used to accomplish the repair is not one of the other root operations. Examples would be colostomy takedown, herniorrhaphy of a hernia, and the surgical suture of a laceration.[24]

- other procedures, including:

- clearing clogged ducts, blood or other vessels

- removal of calculi (stones)

- draining of accumulated fluids

- debridement – removal of dead, damaged, or diseased tissue

Pres-requisites to Safe, Effective and Pleasant Surgery

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy modalities are the different therapeutic techniques, approaches, or processes conducted by licensed mental health professionals to help treat and improve patients’ psychological, emotional, and social well-being.

The purpose of therapy is for clients to: explore beliefs, feelings, and behaviors; address challenging or distressing memories and experiences; obtain better self-awareness and understanding; and develop a plan to achieve desired changes. Individuals seek therapy for many reasons, such as to deal with depression or anxiety, for personal growth and greater self-knowledge, or to cope with major life challenges and traumatic events.

description of Process

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Animal-assisted Therapy

- Music Therapy

- Psychodynamic Therapy

- Hypnotherapy

- Group Therapy

Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy

Psychoanalysis arose from an appreciation of the power of people talking directly to one another about questions that matter and issues that are difficult to understand. In examining what lies beneath the surface of human behavior—in providing multi-layered and multi-dimensional explanations—psychoanalysis teaches us about the unconscious psychological and psychosocial forces that fall outside of everyday awareness.

Psychoanalytic treatment is based on the idea that people are frequently motivated by unrecognized wishes and desires that originate in one’s unconscious.

These can be identified through the relationship between patient and analyst. By listening to patients’ stories, fantasies, and dreams, as well as discerning how patients interact with others, psychoanalysts offer a unique perspective that friends and relatives might be unable to see. The analyst also listens for the ways in which these patterns occur between patient and analyst. What is out of the patient’s awareness is called “transference” and what is out of the analyst’s awareness is called “countertransference.”

Talking with a trained psychoanalyst helps identify underlying patterns and behaviors. By analyzing the transference and countertransference, analyst and patient can discover paths toward the emotional freedom necessary to make substantive, lasting changes, and heal from past traumas.

Typically, psychoanalysis involves the patient coming several times a week and communicating as openly and freely as possible. While more frequent sessions deepen and intensify the treatment, frequency of sessions is worked out between the patient and analyst.

Transference

Transference is a concept that refers to our natural tendency to respond to certain situations in unique, predetermined ways–predetermined by much earlier, formative experiences usually within the context of the primary attachment relationship. These patterns, deeply ingrained, arise sometimes unexpectedly and unhelpfully–in psychoanalysis, we would say that old reactions constitute the core of a person’s problem, and that he or she needs to understand them well in order to be able to make more useful choices. Transference is what is transferred to new situations from previous situations.

As a result, a person’s relationship to lovers and friends, as well as any other relationship, including his psychoanalyst, includes elements from his or her earliest relationships. Freud coined the word “transference” to refer to this ubiquitous psychological phenomenon, and it remains one of the most powerful explanatory tools in psychoanalysis today—both in the clinical setting and when psychoanalysts use their theory to explain human behavior.

Transference describes the tendency for a person to base some perceptions and expectations in present day relationships on his or her earlier attachments, especially to parents, siblings, and significant others. Because of transference, we do not see others entirely objectively but rather “transfer” onto them qualities of other important figures from our earlier life. Thus transference leads to distortions in interpersonal relationships, as well as nuances of intensity and fantasy.

The psychoanalytic treatment setting is designed to magnify transference phenomena so that they can be examined and untangled from present day relationships. In a sense, the psychoanalyst and patient create a relationship where all the patient’s transference experiences are brought into the psychoanalytic setting and can be understood. These experiences can range from a fear of abandonment to anger at not being given to fear of being smothered and feelings of

One common type of transference is the idealizing transference. We have the tendency to look towards doctors, priests, rabbis, and politicians in a particular way—we elevate them but expect more of them than mere humans. Psychoanalysts have a theory to explain why we become so enraged when admired figures let us down.

The concept of transference has become as ubiquitous in our culture as it is in our psyches. Often, references to transference phenomenon don’t acknowledge their foundation in psychoanalysis. But this explanatory concept is constantly in use.

For example, in season three of the television series Madmen, one of the female leads is romantically drawn to a significantly older man just after her father dies. She sees him as extraordinarily competent and steady.

Some types of coaching and self-help techniques use transference in a manipulative way, though not necessarily negatively. Instead of self-understanding, which is the goal of psychoanalysis, many short term treatments achieve powerful reactions in clients by making use of the leader as a powerful, charismatic “transference” figure—a guru who readily accepts the elevation transference provides, and uses it to prescribe or influence behavior. Essentially, this person accepts the transference as omnipotent parent and uses this power to tell the client what to do. Often the results obtained are short lived.

Resistance

As uncomfortable thoughts and feelings begin to get close to the surface–that is, become conscious–a patient will automatically resist the self-exploration that would bring them fully into the open, because of the discomfort associated with these powerful emotional states that are not registered as memories, but experienced as fully contemporary—transferences. The patient is thus experiencing life at too great an intensity because he or she is burdened by transferences or painful emotions derived from another source, and must use various defenses (resistances) to avoid their full emotional intensity.

These resistances can take the form of suddenly changing the topic, falling into silence, or trying to discontinue the treatment altogether. To the analyst, such behaviors would signal the possibility that a patient is unconsciously trying to avoid threatening thoughts and feelings, and the analyst would then encourage the patient to consider what these thoughts and feelings might be and how they continue to exert an important influence on the patient’s psychological life.

As the analysis progresses, patients may begin to feel less threatened and more capable of facing the painful things that first led them to analysis. In other words, they may begin to overcome their resistance.

Psychoanalysts consider resistance to be one of their most powerful tools, as it acts like a metal detector, signaling the presence of buried material.

Trauma

Trauma is a severe shock to the system. Sometimes the system that’s shocked is physical; the trauma is a bodily injury. Sometimes the system is psychical; the trauma is a deep emotional blow or wound (which itself might be connected to a physical trauma). It’s the aftereffects of the psychical trauma that psychoanalysis can attempt to counteract.

While many emotional wounds take a while to resolve, a psychic trauma may continue to linger. When the stimulus is powerful enough–a death, for instance, or an accident–the psyche isn’t able to respond sufficiently through regular emotional channels such as mourning or anger.

Often this lack of resolution can foster a repetition compulsion–a chronic re-visiting of the trauma through rumination or dreams, or an impulse to place oneself in other traumatic situations. Psychoanalysis can help the victim to develop emotional and behavioral strategies to deal with the trauma.

Fortunately, the need for trauma survivors to have treatment is now well understood in the broader mental health community. Certain medications are helpful in the treatment of trauma, but there should always be a psychological component to the treatment, and it must be understood that treatment can be needed years after the trauma is experienced.

Psychoanalysts did much of the early work in treating trauma, from shell shock of WWI, War Neurosis of WWII, Post-Vietnam Syndrome of the Vietnam war, and now Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Treatment of PTSD still contains elements that harken back to psychoanalysis—trauma patients need a witness to their pain, who helps them, bit by bit, incorporate the traumatic experience with the rest of the story of their lives in some way that can make sense. Facing unbearable feelings with another human being, and supporting and employing the ego-the part of the mind responsible for decision making, understanding cause and effect, and discrimination—all these techniques owe their roots to psychoanalysis.

Modalities Used in Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy

PT management commonly includes prescription of or assistance with specific active or passive exercises, manual therapy, and manipulation, mechanical devices such as traction, education, electrophysical modalities which include heat, cold, electricity, sound waves, radiation, assistive devices, prostheses, orthoses, and other interventions. In addition, PTs work with individuals to prevent the loss of mobility before it occurs by developing fitness and wellness-oriented programs for healthier and more active lifestyles, providing services to individuals and populations to develop, maintain and restore maximum movement and functional ability throughout the lifespan. This includes providing treatment in circumstances where movement and function are threatened by aging, injury, disease, or environmental factors. Functional movement is central to what it means to be healthy

Occupational therapists (OTs) are health care professionals specializing in occupational therapy and occupational science. OTs and occupational therapy assistants (OTAs) use scientific bases and a holistic perspective to promote a person’s ability to fulfill their daily routines and roles. OTs have training in the physical, psychological, and social aspects of human functioning deriving from an education grounded in anatomical and physiological concepts, and psychological perspectives. They enable individuals across the lifespan by optimizing their abilities to perform activities that are meaningful to them (“occupations”). Human occupations include activities of daily living, work/vocation, play, education, leisure, rest and sleep, and social participation.

Matching Treatment with Service Delivery Systems

z

Proudly powered by WordPress